ctors wielding them.

Instrumental deliveries in hospitals were mostly devoid of even ordinary cleanliness. Aseptic and sterile practices were not utilized during and after deliveries due to ignorance regarding the existence of bacterial or viral pathogens in the birthing environment. Likewise, antibiotic and antimicrobial treatments had not yet been developed. Many new mothers died of puerperal (birthing-related) infections. Maternal mortality ran rampant in the “skilled” obstetrics wards where the idea of a normal pregnancy and delivery was considered a fallacy.1

New OB Hospitals Escalate Maternal Mortality

Maternal mortality rates in the new OB hospitals became so high that a White House-sponsored public health conference was convened in 1925 to address the problem. Statistics collected from the conference confirmed that women who delivered with midwives were not subject to the devastating morbidity and mortality of women who were delivered in hospitals by obstetricians.

The White House study also concluded that hospitalized women in America had increased incidences of childbirth interventions which resulted in maternal and infant mortality statistics that were significantly higher than those collected in Europe, where midwives were accepted as competent healthcare providers and had the opportunity to practice. Despite the findings of this conference, modern obstetrical medicine prevailed over home-centered midwifery care.*

Male Physicians Obliterate Midwifery

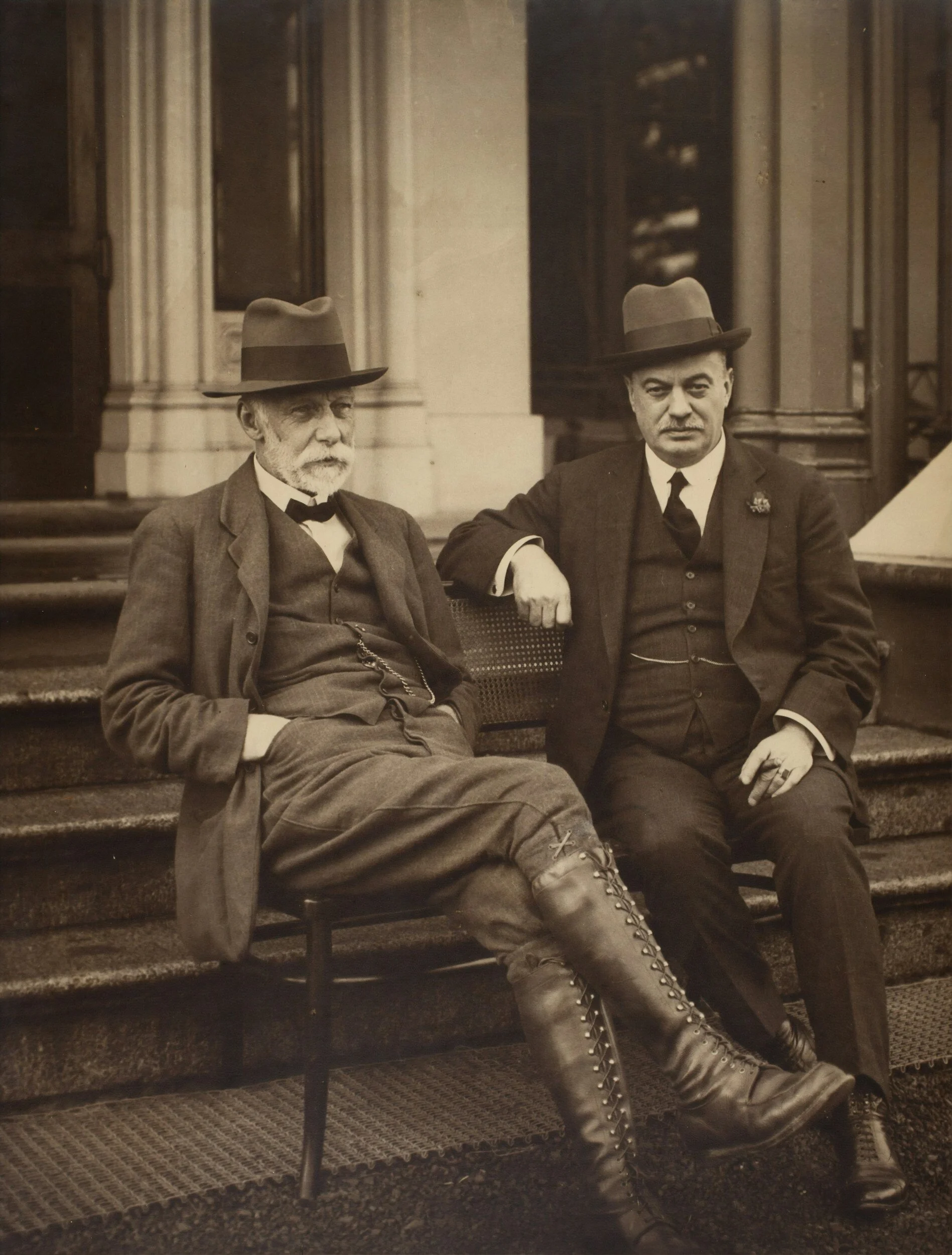

Midwives were incrementally banned from obstetrics wards by male physicians. Allopathic medicine (MD educated) became popularized and promoted by wealthy industrialists who interacted socially with medical doctors within the upper echelons of society.

Other specialist health care providers, such as nurses, midwives, homeopathic and botany-based healing practitioners, were relegated to caring for “lower classes” of Americans. One bastion of allopathic medicine was the famous Johns Hopkins Hospital. That entity was active in establishing MD-trained doctors as the predominant profession for providing acceptable health care.

Eventually, nurse-midwives were excluded as legitimate providers of “professional” healthcare and were left to attend women living in rural, isolated areas and assist childbirth in tenements of the inner-city poor. At the turn of the 20th century, American MDs were fighting hard to abolish what was left of American midwifery. In 1920, Dr. Joseph B. DeLee published a famous article titled: “The Prophylactic Forceps Operation”.

**And He Called the Midwives Barbarian. . .

This article describes the surgical incision that was to become known as an episiotomy. It was promoted by male doctors as a preventive procedure to avoid serious perineal tears and prolapse of maternal reproductive organs. Detailed descriptions of the “operation” outlined high points of the procedure, such as the generous use of narcotics, disorienting anesthetic gases, and metal instruments to pull the baby from the womb.

In addition, generous cuts, from vagina to rectum, were previewed along with administration of the drug oxytocin, which was utilized to stanch the inevitable hemorrhaging provoked by the mechanical manipulation of a woman’s uterus, cervix, and pelvic floor soft tissues. Dr. DeLee created video presentations highlighting the use of forceps, stating, for the record, that: “It’s not the forceps, but the man behind the forceps, that matters. In his scholarly papers, Dr. DeLee was emphatic regarding the evils of midwifery, referring to midwives as “relics of barbarism.***

The Extinction Phase of Midwifery

By 1930, only 15% of births were attended by midwives. In contrast, European and Scandinavian countries were embracing obstetrics for pathological deliveries but were supporting schools for the education of midwives. Dual systems of maternal care were developed where midwives continued to attend uncomplicated, normal births, and the obstetric consultants were summoned for complicated, high-risk deliveries. 2

Hospital Birthing Became Popular With Society Women

During the late 1930’s and early 1940’s, American women became particularly attracted to hospital care for childbirth. As a consequence of most women’s understandable fear of pain and death in childbirth, the promise of a safe and pain-free hospital experience became irresistible. By the 1940’s, over half of births took place in hospitals. By 1951, 90% of births in America took place in hospitals with obstetricians. By mid-century, American midwifery was almost completely wiped out.

During the Women’s Movement of the 1960’s and 1970’s, pregnant women began to demand more flexibility in hospital childbirth. However, those who wanted less medical intervention during their childbirth experience were frequently frustrated by the lack of cooperation from hospital staff. Hospital nurses, in particular, were reluctant to participate in “un-medicated deliveries, considering the demands of women desiring a “natural birth” to be radical and unsafe. During this time, cesarean deliveries were common, occurring at increasingly high rates despite a lack of scientific evidence demonstrating that routine surgical interventions had little effectiveness in improving maternal-child health. 3

Why Is It Still Such a Fight?

Over time, nurse-midwifery practice was, reluctantly, allowed to return to hospitals and clinics. This did not occur without a fight. In many ways, it is still a fight. The tenacity and conviction of dedicated CNMs forged the way for so many practicing today. Unfortunately, negative attitudes and overt condemnation by physicians created a difficult environment in which to practice. Labor and delivery nurses, prejudiced against CNM care, felt justified in refusing to care for nurse-midwifery patients, claiming that their participation made them vulnerable to lawsuits. There was no basis in fact for these claims, but they served as a convenient excuse to avoid caring for difficult midwifery patients. Hospital administrations supported these behaviors, which further stressed the working environment.

Against all odds, nurse-midwifery prevails, although battle-weary. Professional midwifery practice has modestly proliferated over time, but remains in jeopardy due to the persistence of uninformed and hostile attitudes among hospital administrators, medical, nursing, and administrative staff, and liability carriers. Equally discouraging, corporate healthcare is gnawing away at nurse-midwifery, closing practices, and utilizing CNMs only if it serves financial interests. Additional challenges to practice include the threat of legal liability, high malpractice insurance costs, role-confusion, collegial disdain, and decreasing opportunities to practice while remaining true to a midwifery model of care.

1. Suarez, SH. Midwifery Is Not The Practice Of Medicine. 1992. Yale Journal of Law and Feminism. 5(2):6 page 327. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yilf/Vol 5/Iss2.

2. These systems of care exist today in Europe, Scandinavia, and around the world, where midwifery units attend to uncomplicated pregnancies and deliveries. Depending on acuity, when laboring women develop complications, they are transferred a short distance to the consultant units for care. Even in higher-risk units, both midwives and physicians can work together to care for patients.

3. Brodsky, supra note 13, article 6.

* Judy Barrett Litoff; Forgotten Women: American Midwives at the Turn of the Century. The Historian. Vol. 40. No. 2 (February 1978), pp. 235-251.

** The Prophylactic Forceps Operation (1920), Joseph Bolivar DeLee. American Gynecological Society (1920): 66-83.

*** See above

https://www.midwivesontrial.com.

Significance For Practice

Relevance:

Understanding the evolution of midwifery practice and gaining perspective on how societal attitudes toward midwifery legitimacy have evolved (or not) is essential to establishing and understanding your role and responsibilities in maternal healthcare. In the context of where nurse-midwifery has been and is currently heading, maintaining their identities in corporate healthcare has become difficult. CNMs/CMs are struggling to preserve a distinct role in modern maternity care. Protecting midwifery identity in the midst of rapidly evolving corporate needs for qualified maternity care providers will be an ongoing challenge for newly graduated (and veteran) CNMs/CMs.

Situation:

Professional distrust of midwifery by colleagues/hospitals remains pervasive, yet CNMs/CMs are being used as physician extenders and surrogates to fill provider vacancies (particularly for night shifts) in acute care settings. Maintaining fidelity to a midwifery model of care and to a midwife's identity is increasingly difficult in hospital practice. Midwives are functioning like physicians in many acute situations but are not appropriately compensated or supported. Hospital financial interests frequently jeopardize safe care.

Vulnerability:

Role uncertainty and confusion with decreasing opportunities to practice utilizing a midwifery model of care. Confusion regarding your role (and potential liability risk) in acute care situations.

Considerations:

It is important to define your role and responsibilities in every care situation. It may be necessary for you to decide how you want to identify yourself, as a midwife or a physician extender. Find ways, in acute non-midwife care situations, to provide any version of midwifery-centered care, when possible. It is entirely appropriate to maintain the heart and patience of a midwife, even while initially managing or participating in a high-risk delivery. Take the time to imagine ways you can still apply a midwifery model of care while safely and competently functioning in less-than-normal OB situations.

© 2024 Martha Merrill-Hall